Gift of Love-The

Life & Times of Sam Sanders

(The

Greatest Unknown Saxophone Titan in Jazz History) By Mark P. Brown

Detroit Michigan-Winter 1974

Chapter One

Taking the last gentlemanly swig from a small bottle of Hennessy and

turning off the motor in his rust-orange Mazda ‘Rotary’ compact four door sedan

Sam Sanders Jr. looked at me with those intense, big brown warm eyes and said,

“Now don’t’ forget, it’s been over twenty years since a white person has been

inside my parents’ home. I’ve told my mother (Mary) and father (Sam Sanders

Sr.) all about you and why they should welcome you. You’ve got to understand

though, even if you really can’t imagine it no matter how much you love me,

what they’ve been through…what they’ve seen. C’mon let’s go, just be yourself.”

“I’ll try. Who else could I be?”

While sitting in front of the neat, spotlessly maintained corner

two-story fenced home at 13571 McDougall St. in Detroit’s near East Side, one

block off of the Fisher Freeway, I remembered what he had relayed to me about

the incident that resulted in white peoples’ banishment. Even if it were

medical or fire personnel it didn’t matter, they were forbidden to enter into

the sanctuary. It seems that the white former owner had sold the house to

‘colored people’ without settling his electric bill with the city and this

burly white municipal employee showed up knocking loudly on the door. He aimed

to collect it from the Sanders and his demeanor spoke loudly about how he felt

seeing this old Slavic neighborhood ‘integrated’.

It’s really unknown what transpired or what was said but to a humble hard

working couple like the Sanders who had toiled as the saying went, ‘From

can’t to can’t’ (so early in the morning it was too dark to see, until so

late at night is was the same) to own their own home it was sufficient to

poison the waters for the intervening years.

Sam Sanders Sr. was born in the racially treacherous Deep South early

after the turn of the 20th century in an unincorporated area on the

outskirts of Birmingham Alabama. Home was a ramshackle clapboard structure with

no electricity or running water and dirt floors. Between the savage ‘Night

Riders’, bands of roving Klu Klux Klan members terrorizing, robbing, raping,

beating and hanging black people routinely and with impunity as their

“Christian White Supremacist’ right, hell on earth was being made worse by the

cruelly pervasive Jim Crow laws which were tacitly being enforced by the local

police. Segregation on its own was psychologically, spiritually, mentally and

physically stifling and heartless enough without the constant torment of living

in an endless state of fear. Legend has it that his family boarded him onto a

cattle train with nothing but the clothes on his back and sent him to live with

a relative in Detroit to spare him the insanity of their life in Alabama. He

was ten years old.

Much has been written about the ‘Greatest Generation’ chronicling

the period spanning the Great Depression through and including World War Two

and the ensuing unprecedented and unequaled post war achievements of this era’s

extremely patriotic, devoutly American (in the Alexis de Tocqueville sense)

pre-socially engineered class group. My only issue with this richly deserved

legacy is that it either is unintentionally oblivious to the equally great

contributions of blacks of this same period or, more bluntly, just another

whitewashed accounting in our history designed to patronize the selective

exclusivity of the Anglo Saxon pervasive majority perceptions before, during

and after all of this happened.

It is important to note that in this dawning of the 20th

century, barely fifty years since the so-called, widely misinterpreted

‘Emancipation Proclamation’ of 1863, blacks were not 1% better off than before

Lincoln issued his Presidential Order which in truth was based solely on Civil

War strategies. The perception of Lincoln as the Moses figure filled with

virtue and Christian empathy just doesn’t jibe with the facts. The Confederacy

was clearly winning the war at this time and Lincoln’s instincts were driven by

logistics and pragmatism not some epiphany inspired by the hand or voice of

God. Lincoln’s order intentionally preserved slavery in the Union States and was

designed to effect only the four million slaves living in the Confederate

States with a hoped for military result which without question is the sole

reason the Union prevailed at all.

The facts are that it affected only those slaves that had

already escaped to the Union side. As the Union

armies marched into the South, in the territory they were able to control and

bring under Union dominion, slaves received their freedom. Tens

of thousands of slaves joined the Northern Army because they knew

that with a Northern victory came freedom.

If it not been for African-American slaves who took up arms and supported

the Northern Army, the North would not have won the Civil War. You can glorify

Lincoln, Grant, Sherman and a slew of other Civil War Generals and Heroes of

the Union Army, but at the end of the day slavery was abolished, not by these

venerated white male protagonists but rather by African American slaves

themselves who could no longer live with the iron chains of slavery wrapped

around them.

It was into this black ‘Greatest Generation’ that Sam Sanders Sr. and his

angelic, serene wife Mary along with nearly the full majority of their peers

who somehow took the blows, insults and injuries from this still violently

racist country and nonetheless triumphed. This forgiving, willing,

accommodating and congenial first generations’ ‘freed men’ with their lion

hearts on their sleeves and proud heads held high, eventually won a less pyric

victory with the grudging support of significant elements of whites with the

passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

Chapter Two

In the post-Depression United States the music that each generation black

or white listened to was woven into the textures of the prevailing human

circumstances of each. Historians theorize that American music evolved from the

distinctly different cultures and racial components on the two starkly

contrasting sides of the mighty Mississippi River which runs from Canada all

the way into the Gulf of Mexico. The nations’ population in 1920 was approximately

one-hundred and five million with over 85% living east of the Mississippi.

You can start heated arguments over where such idioms as The Blues, Jazz,

Country Western, Rhythm & Blues, Bluegrass much less Pop Music originated.

Early film and music both served as windows for the masses to romantically view

their collective surroundings and escape their punishing realities with radio far and away

the trailblazer. By 1928 radio had gone nationwide with three major stations

and hundreds of affiliates. Simultaneously silent films were giving way to

‘talkies’ with, ironically, the first major release in 1927 of “The Jazz

Singer”. It had Al Jolson in the lead role as a rebellious Jewish crooner

trained to be an Orthodox Jewish cantor who gets the itch and starts singing

Jazz in black face no less!

Particularly in mainstream pop culture music the common ground of all of

these idioms was their projecting the desires, sufferings, uncertainties and aspirations

of each specific strata. In the 20’s and 30’s the suffocating poverty and

aftermath of the Depression resulted in music that intended to lift up and help inspire people. In the 40’s

coinciding with the trauma of everything from WWII, the country’s first ‘race riots’

and ultimately the nuclear obliteration of Hiroshima and Nagasaki popular

mainstream music started to markedly separate itself along (go figure) class,

economical, educational and of course racial lines.

The nations’ population growth had continued to move West and South so it

was no coincidence that New Orleans and Kansas City became the newest trend

setting hot spots accentuated by their large black populations and evolving

styles unique to them. This was now anathema in its opposition to the syrupy,

rigid, comparatively joyless music that whites listened to for the most part.

Things were really changing quickly in black America while white America was desperately

trying to hold onto the past to the point of piously ignoring and denigrating

these new idioms.

Music critics of this era haughtily vilified jazz and blues music as

being somehow primitive and unworthy of general acceptance and mainstream

success referring to it as ‘race music’, ‘barrel house or speakeasy music’

(translation: whore house) all code for and just short of flat out calling it

‘nigger music’. What they didn’t notice or chose not to see was the huge wave

of popularity of this music with young white kids everywhere. With the coming

of Rock ‘N Roll the crossover cultural last straw saw the cat leaping out of

the bag from then on. Imitation being the highest form of flattery this didn’t

stop white America and the fickle hypocritical music business hustlers from

trying to pretend that this genre was somehow not mutually inclusive. No

greater example of this was the relentless promotion and myth building that was

the Elvis Presley phenomena.

Already well defined and underway was the non-apologetic, no Steppin’

Fetchit’, goodbye pork pie hat, straight ahead be-bop explosion with the space

exploring tradition shattering Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Lester Young

and Dexter Gordon leading the charge eventually influencing even the great former big band

generation of innovators like Duke Ellington and Count Basie to opening their

talented ears to this sea change too. This late 40’s early 50’s bull rush

spawned the next generation of envelope pushers with Miles Davis, John

Coltrane, Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, Sonny Rollins, McCoy Tyner, Charles

Mingus and too many more to mention setting the bar as high as it ever got and

signifying the Golden Era of Modern Jazz.

Sam Sanders prime came along right after these icons and titans beginning

in the mid-sixties but with windows closing and doors slamming shut for many,

many reasons, not the least of which was the 60’s for better or worse ushered

in the inclusion of ‘politics’ into all media driven commercialized musical

forms except perhaps classics and opera. Nothing could have been more chilling

as it also attracted the new corporate monsters into the industry’s highest echelons

and the mix for genuine artistry and real expression was toxic and deadly

almost immediately. As I’ve noted before it’s a long way from Johnny Hartman to

Cool Moe Dee and from John Coltrane to Kenny G.

R&B also had enjoyed its creative zenith during this same time frame,

yet sank like a stone with the aberration that was Disco and it’s funeral pyre

could be seen wafting over the landscape with the bottom of the toilet that

was/is Rap Music. Jazz? Literally gone without a trace other than as a

historical timepiece or worse a college lab driven study class where the notion

that it could be taught like math has martinized the form into the vapid empty

vapor it has become.

Which is certainly not to insinuate that Jazz couldn’t be taught or

passed down from one generation to the next. After all it was at Oakland

University in 1973 that I met Sam Sanders as another neophyte want-to-be

saxophone aspirant. The distinction was that until the melting pot melted

everything into a tasteless soulless vanilla you had to have lived a little,

ran wild in the streets some, tasted the blues, had your ass kicked and your

dreams shattered, got knocked down but not out before any instruction would

help someone like me make something beautiful where before there was none.

Sam Sanders used to describe this progression as, “What comes out of the

bell of the horn after you’ve learned how to play… is the Life you’ve lived,

who you really are, what you honestly believe in and how you feel about it.”

Chapter Three

Of this never ending morass that is the discussion and analysis of the persistent,

seemingly solution immune racial problems still dogging our society, when one

reads these first two chapters introducing the stories sub-byline they might

conclude that the author is somehow above the fray and unsoiled by the cancers

of intolerance, mistrust and spite that pockmark its participants friend and

foe alike. Nothing could be more of a willful, dishonest charade and absolute

violation of a writers’ oath to the craft, himself and his readership.

I’m uncertain whether these personal negative trends are the spiritual

corpulence of aging, manifestations of a long dormant, latent infection in my

soul or the enormous gravity and weight resulting from the socially re-engineered

divisiveness being fomented from the top down which rain nuclear hateful

snowflakes on us all 24/7. Either way, I’ve got it too, and sometimes it’s so

ugly I can’t stand to listen to myself talking or thinking the horrible bile

and stink that are sometimes my own demonic racial opinions and attitudes. If

you think that you’re immune and lily white clean of this conundrum and

spiritual influenza I suggest you stop reading immediately and teach us all how

to fly. This story is not however a primer on race in America.

It is devoted to what Sam Sanders life and music meant to all of the

people lucky enough to have heard him and especially those fortunate souls who

got to know him. Sam was an eternal flame not just a light that by planned

obsolescence eventually flickers then fades away even from memory. Those few

chosen ‘Originals’ never go out of style or become irrelevant nor stuck like

glue to a particular place or moment in time. Sam was like this in every

respect. The instrument itself was so dominated by Bird and Trane that after

they visited generations of really excellent players nonetheless sought to

imitate rather than initiate mostly to their detriment. Sam Sanders was no

imitator. A pure original.

Sam used to preach to all of his students that there were three

components that ‘artists’ tailored to their own footprints. “Sound, technique

and voice.” He always made the scornful distinction between the ‘artist’ and

the ‘musician’ by defining the latter as “anyone who got paid $5 to play”,

verses those who “make you want to listen.”

Just as the combined ‘Greatest Generations’ built things that lasted and

endured yet they paradoxically

fathered the insidious ‘Baby Boomer’ weaklings who selfishly looked mostly on the souls outside for their

inspirations. Thus overlooking the most essential ingredient, the salt of

humankind, in order to produce their endless choices of flavorless dishes, so

it continues to march on to afflict artistic expression.

These master Boomer self-deceivers subsequently then produced the

listless robotic X, Y and Millennials who for the most part can barely talk to

one another and won’t and can’t look a man in his eyes. So it should not be a

surprise that we live in a retro ‘Oldies’ culture especially as it relates to

the arts. Vast periods of aridity and emptiness have taken place down through

the ages but the last forty years or so is unprecedented and there are no

revivals or comebacks in sight.

What really made Sam Sanders music so authentic and original was his use

of hard earned applied skills honed over thousands of hours of practice and

exploration with the secret ingredient being the injection of the home grown

unmistakable Detroit/Motown soulfulness into his otherwise post-Avant Gard

compositions. Make no mistake this was a Detroit thing and other cities had

their own styles and sounds too, but nothing like the urgency, backbone and

bluesy soul like Detroit’s. Guitar virtuoso Carlos Santana says that his path

as a musician and spiritualist had three steps in evolution, Love, Devotion

and Surrender. Loving is the foundation, devotion is the structure,

surrender is the desired result.

For example Marvin Gaye possessed several well-honed sounds, techniques

and voices such that his vocal range and gut wrenching recordings bore close

resemblance to musical instruments themselves. To the same degree Sam’s

offerings were more like someone ‘singing’ the saxophone rather than just

‘playing’ one.

One of his protégés Christopher Pitts once said of Sam,

“He was very insistent on individuality, never had you copy solos. Of all of

Sam’s students nobody sounds alike or sounds like him for that matter.” When I

became a disciple in 1973 at Oakland University’s School of Music the

collection of future virtuosos under his tutelage included Vincent Bowens, Kenny

Longo, Racey Biggs, Pete Wenger, Gary Bubash, Steve Wood, Scott Petersen, Eugene Mann, Mark Hershberger and

many more. Although one would think it not remarkable Pitts points out that Sam’s

students as well as subsequent ensembles such as the Pioneer Jazz Orchestra

(1980-1990’s) were always a mix of racial and ethnic backgrounds. By contrast

most of the big bands in Detroit in this era were either all black or all white

with only the Pioneer Jazz Orchestra 50-50 with no distinction of any kind

other than acumen and commitment.

The environment at this time in sleepy Rochester MI was accentuated by

the unlimited passion of program director Marvin ‘Doc’ Holliday who had come

off the road after many years touring with the likes of Thad Jones & Mel

Lewis Orchestra, Duke Ellington and many more. Doc was principally a baritone

saxophonist but I loved his playing on the soprano as well. The staff he put

together at O.U. read like the ‘who’s, who’ of Detroit jazz. Sam Sanders, his

jubilant fun loving drummer Jimmy Allen and bassist Ed Pickens which became the

core of his acclaimed ensemble “Visions” along with the legendary trumpeter

Marcus Belgrave - who played with everyone from Ray Charles, Charles Mingus, Ella

Fitzgerald, Tony Bennett and his mentor Clifford Brown - Harold McKinney (keyboardist),

Ali Muhammad Jackson (bassist), were the

mainstays and ‘guests’ included trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, Frank Foster

(saxophone), Clark Terry (trumpet), Phil Woods (alto saxophone) and other

luminaries.

Make no mistake though the lightning rod for the students regardless of

degree of proficiency or chosen instrument was Sam Sanders, Jimmy Allen and Ed Pickens.

Although cordial, patient and accessible to everyone very few of us neophytes

were included in their social and/or anti-social activities.

The drive from Rochester to Sam’s home in Detroit was only thirty miles

and barely forty five minutes away but for all but a lucky few may as well have

been two states over. Even fewer were invited to participate in Sam’s legendary

nerve wracking rehearsals in his crowded, steamy basement where, like the

boxing gyms in Philadelphia where the sparring sessions were tougher than the

sanctioned fights elsewhere, the mettle of any musician who had the balls to

play would be tested to their limits.

Much like the 1940’s notable eccentric Milton “Mezz” Mezzrow who,

although in reality just a so-so saxophonist just like I was, nonetheless

became the great Louis Armstrong’s favorite running buddy and sidekick, I

managed to quickly become a fixture within the comings and goings of “Visions”.

With Sam (mostly by day) and Jimmy Allen (all night long) our friendships

eclipsed the traditional roles to the extent that within a year they challenged

me to stop parachuting in and out of their neighborhood and ‘put up or shut up’

and move down into the ‘hood.’

Chapter Four

Jimmy Allen was a mercurial and, for those who didn’t know him well,

somewhat mysterious man two years older than Sam. Coltrane’s drummer and fellow

Detroiter Elvin Jones often said that Jimmy was the best at his craft anywhere. Tall, dark and handsome Jimmy

had lived by choice on the edge of the mainstream culture and society. No one knows how old

he was when heroin became a situation but it did dog him for most of his entire adult life.

He knew how to work the system though and avoided the dreaded Jones by being a

daily attendant at the local clinic where they spiked his orange juice with the

cure. Unlike his older brother, also named Sam, who was a graduate of Jackson

State Penitentiary Jimmy steered clear of trouble and the police whom he

despised. He could repair everything from watches to washing machines and cars

were afraid of him. Armed with only a wrench and screwdriver he would take cars

believed to be in the throes of death and restore them to happy owners to drive

another day.

I have no idea why but ninety-nine percent of the time when Jimmy Allen

addressed me he would start and end each sentence with, “Mother Fucker” this

and M.F. that. By no means was it hostile but in truth was just the opposite and

I proudly knew how much Jimmy accepted and loved me when he would call me ‘his nigger’.

In this scenario it was the highest form of a term of endearment especially to

a blue-eyed, untamed wild man white boy like yours truly. So one day after

rehearsal when everybody was heading out the door, Jimmy Allen nodded to Sam

and said to me, “Get in the car Mother Fucker let’s go for a ride. We’ve got

something to show you.”

Once inside the reefer got passed around (Sam never partook) and the

cognac rotated likewise as we headed over towards Gratiot Ave. I thought we

might be going to ‘Bert’s Black Horse Lounge’ one of our nightspots when

instead of stopping on Gratiot we turned right on Iroquois St. and parked in

front of Jimmy’s four-plex.

Jimmy’s wife Vita a tall, skinny woman who I never, ever saw wearing

anything except her bathrobe and slippers, and a real character in her own

right, was standing at the top of the stairs. “Y’all are crazy especially you,”

she not-so-cheerfully announced staring wearily at me. Handing some keys to

Jimmy she said, “It’s cleaned up, painted and the power is on. Everything’s

cool except they’s still rats in the kitchen. I set some traps for ‘em those

nasty mother-fuckers.” Jimmy opened the door and Sam and I followed him inside the

antiseptic sparkling clean totally empty two bedroom apartment.

“The rent is $125 a month mother fucker and we paid it for you. Here’s

the keys. Now whatcha gonna do?” The two

of them just laughed and began forecasting how long I’d make it until I ran

back out to the suburbs.

“You’ll see, I’m here for a while. After all I work just down the street

(waiter/busboy at Joe Muer’s Seafood Restaurant on Gratiot Ave.), I’ll be the

most popular white boy in the neighborhood once the locals get a taste of my reefer,

I’ve got Teaser and Flip ( father and son Doberman’s) as security, plus you

guys did this to challenge me. I accept. Thanks!”

I stayed for over one year and it was an experience I wouldn’t trade for

gold bars. Within a month I had a flourishing weed business which allowed me to

get to know quite a few of my neighbors to say the least. From factory workers,

retirees to pensioners the folks would knock on the door for amounts as small

as an old school $5 ‘nickel bag’ and many of the women would bake sweet potato

pies and bring fried chicken, collard greens, black eyed peas and corn bread

with them too. I’d walk the dogs around, all two hundred and twenty five pounds

of them, and no matter how many times I’d tell the people that they were

‘friendly’ only small kids would venture over to pet them.

Every now and then Jimmy and I would ride around the hood and when he’d

see the young bloods up to no good he’d call them over to the car, point at me,

show them his gun and inform them that, “This here is my boy. Fuck with him at

your own risk because it’s just like messing with me. Got it?” In the last

analysis I got along better living on Iroquois St. than I had anywhere before

out in the burbs. Not one single white friend ever visited me and I can’t say

that I missed them.

One snowy cold day Vita Allen knocked on my door and handing me $4 asked

me to run down to this crappy corner market and, “Bring me three pounds of

chicken necks and backs.” Upon my return she opened their door across the hall

from me and an intense wave of scalding heat hit me right in the face. Jimmy

was asleep on the couch with the TV blasting and Vita and their daughter were

in the kitchen. Our rent included utilities so nobody worried about the bill. I

looked at the thermostat which was set on ninety degrees. Handing her the

chicken I asked why in the world was the heat on so high and hot.

“What business is it of yours’ mother fucker? Jimmy says you used to live

in Hawaii, right? Well I ain’t going to Hawaii anytime soon so if I want to relax

in tropical heat jus’ shut your mouth. OK?” It was a Sunday and she said,

“Dinners in one hour so don’t be late!”

“I’ll bring my bathing suit and some sand.” I remember it as one of the

most delicious meals I’ve ever had.

Chapter Five

That spring Sam took Visions which now included keyboardist

extraordinaire John Katalenic into this Detroit studio owned by a guy I knew

from the burbs named Jackie Tann, a real wanna-be who had money but no real

talent at producing or recording music. Sam decided that for better or worse he

would suffer Tann’s deficiencies in order to get the tracks laid down.

We were planning a Fall trip to New York’s major recording labels with me

dressed up in suit and tie as their agent and I had talked my way into

appointments with the likes of Clive Davis at Columbia Records and Ahmet

Ertegun at Atlantic Records. I had the complexion and the connection.

Tann finally wore out Sam’s patience and a young guy named Donald Fagenson,

whom I knew from my old neighborhood, stepped up and in his modest basement

studio in Oak Park MI recorded Visions with great skill and success in this his

first major artist sessions. Donald Fagenson would later become ‘Don Was’ one

of the most acclaimed record producers of all time. His credits include the

Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Bob Seger, Joe Cocker, Count Basie and literally

everyone who had prominence in the music business for the last forty years. These

recordings included some of Sam’s most compelling and beautiful works

‘Fantasy’, ‘Kindred Spirits’, ‘Face at My Window, ‘Close Your Eyes’, and

‘Summer Mist’.

That May Visions began an extended Wednesday through Saturday gig at a

new Jazz club in the lobby of a nondescript office building in drab Southfield

MI called ‘The Perfect Blend’. The “Sixth of March’ , ‘Madame Butterfly’,

‘Vacant Eyes’ and the ode to his mother “Marie’, and one titled simply ‘The

Blues’, all new Sanders compositions, were added to the seamlessly flowing set

in front of sparse but wildly appreciative audiences. I recall that most nights

the thirty or so patrons were for the most part his students and ardent

youthful followers who were either teetotalers or so broke that they could only

afford a draft beer which was nursed for hours. The only thing as tough as

being a jazz musician was being a jazz club operator.

On Friday and Saturday night the club would be standing room only and

whomever was playing at Bakers Keyboard Lounge would suffer. By then

Bakers was no longer Carl Bakers personal passion and the new owners (Mr. Baker

would sell and then buy back several times over until 1995 when he finally gave

up) were sinking the ship quickly with non-top shelf circuit players in between

Chicago and New York skipping Detroit altogether or playing in Ann Arbor where

legendary Detroit bassist Ron Brooks had helped open a jazz club.

Ann Arbor also was home to ‘The Blind Pig’ where I had the honor

of playing with crazy Dave Swaim’s big band along with Brook’s ‘Bird of

Paradise’ and ‘Mr. Floods’. In other words Detroit’s jazz and blues

nightclubs and their historic scene and vibe were essentially gone without a

trace.

That September we headed to New York in a cramped old Buick “Deuce &

Change” 225 and drove the Canadian route and landed in The City at the famed

‘Musicians Lodge’ aka The Wellington Hotel at the corner of 42nd St.

near Times Square. If you had a musicians’ union card you could stay at the

Wellington already a cheap hotel to begin with really on the cheap. If you

wanted to practice your instrument, dance routines or orchestral ensembles up

to 10 PM you had to stay on floors 25 thru 30. From floor 31 to the roof you

could howl, stomp and wail all night as it was OK with management. As we were

checking in Sam recognized the legendary alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman and

said hello. He had lived at the Wellington for many years.

I recall that our itinerary involved cramming a tremendous amount of

events, meetings and reunions into three days and two nights as even though it

was 1975 a cup of coffee in Manhattan cost $4. We arrived on a Wednesday and my

first appointment at Columbia Records with the renowned producer Clive Davis

was at eleven in the morning followed by my meeting with Atlantic Records and

equally renowned producer Ahmet Ertegun at Atlantic Records at one o’clock that

same afternoon.

Mr. Davis had recently formed Arista Records specifically to branch into

non-traditional musical forms relative to the parent companies musical format

which was then primarily rock ‘n roll, folk and classics. We were told that he

had a real sympathetic ear for jazz talent but in reality was mining for

commercial success vehicles only. In retrospect Davis thought that the

excellent R&B band ‘Earth, Wind & Fire’ was by his definition

“Jazz” which foretold the sad coming of the ‘Soft Jazz’ sound and its

moribund proponents the likes of Boney James, Ronnie Laws, David Sanborn and

the aforementioned horrific Kenny G.

This watered down elevator music was then peddled to the Boomers as jazz.

Mr. Davis listened to several of Sam’s recordings and he may have been able to hear the genius and true artistic expressions

in it but the cash register in his mind did not jingle. That he is ‘acclaimed

and credited’ for having furthered the careers of saps such as Barry

Manilow, The Grateful Dead, Air Supply and Carly

Simon says it all.

Ahmet Ertegun was an altogether different sort of record producer and

person. Like Davis and Columbia/Arista he had shareholders and was beholding to

profits and commercial music but due to his own musical training and tastes can

be credited with the recording careers of Ray Charles, Aretha

Franklin, Big Joe Turner and B.B. King to name a few.

His success at Atlantic Records enabled him to create the Memphis-based Stax

Records and opened the doors for such blues greats as Sam & Dave,

Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding, Solomon Burke and

many others of this genre.

All the while though keeping his finger on the pulse of the bigger market

commercial trends he also brought Led Zeppelin and Crosby, Still,

Nash & Young to Atlantic Records.

Mr. Ertegun sat back in his chair when we listened to Visions demo

recording occasionally looking at me nodding his head in approval.

There were four songs reduced to three minutes each as the advice I had

been given clearly mandated such limitations. Davis fast forwarded all four

tunes and probably heard five minutes of it at best, whereas Mr. Ertegun

listened to the entire tape. The final song, the tenor saxophone pleading

ballad ‘Fantasy’, had him closing his eyes and then replaying it saying, “His

sound is so unlike others of his era, so lyrical and lovely to listen to.” Then

finally, “Ah, those Detroit players are like no one else anywhere on Earth, so

raw and emotional.”

As our meeting ended this kind and wonderful man who was born in Istanbul

Turkey, educated in London and had tasted so much fine music over the course of

his career looked at me with great empathy and said, “I can tell how much you

care for Sam Sanders and want to see his music reach the worlds ears and I know

there is a place for him somewhere…but at this time not with Atlantic Records.

Keep sending me more of his recordings as they occur and I’ll keep the faith

and listen. I personally loved it but…..”

Sam, Jimmy and Pickens were waiting for me in the lobby of Mr. Ertegun’s

top floor offices overlooking the skyline of The City and I did manage to wait

until we got into the elevator before starting to choke up.

“I let you down. He said no, not at this time. Just like Davis did.”

Jimmy immediately said not to be a wuss, stop whining and stand up

straight, while Pickens sort of glazed over muttering, “Man, you tried, that’s

all we can ask for.”

Sam bear hugged me and while consoling me was in true character

unapologetic and defiant. “Fuck ‘em. We aren’t changing a damn thing. Let’s go

drop off the other tapes and be done with it.” So we headed to the offices of

Impulse Records, Prestige and Blue Note where I didn’t have appointments so

much as producers willing to listen and get back to us.

Chapter Six

That evening we had been invited by the great avante garde guitarist James

‘Blood’ Ulmer a native Detroiter and longtime friend of Sam and Jimmy, to his

loft in the East Village for dinner. In that music critics were tone deaf to

anything outside the concrete box his guitar style was described as ‘jagged and

stinging’ and his singing panned as ‘raggedly soulful’. To jazz fans worldwide

he was a more authentic version of Taj Mahal whose bluesy nursery rhyme songs

were a hit with mostly young white audiences. Ulmer’s career started with joining

forces with the aforementioned Ornette Coleman, and later the likes of Pharaoh

Sanders, Sam Rivers and George Adams. Not surprisingly he was exponentially

better received and popular in Europe and the Orient than stateside. We ate

like Kings and had a ball.

The following day we headed up to Harlem to visit this bundle of brains,

beauty, energy, spirit and purpose named Viola Marie Vaughn. Although Sam had

been married many years before to a Detroit woman named Ollie with whom they

had a son Alim Khan Sanders, he was essentially a single man when we met. Viola

would become his wife, confidant and advisor for the rest of his life.

Viola was born in Little Rock Arkansas in 1947 to the Rev. Dr. Wensel

Rumble Vaughn and his wife a school teacher also named Viola Marie Vaughn. She

graduated from Hampton University with BA’s in both French and Music and from

there went to Columbia University Teachers College in New York where she began

her stellar career in health related fields receiving her doctorate the following

year after our visit in 1976 and eventually a second doctorate in 1984 in

International Health Program Planning.

She had traveled the world extensively but is was Dakar Senegal that

captivated her heart and soul and where she and Sam eventually emigrated to in

1990. Her family had relocated to Detroit when she was a teenager and she

shuttled back and forth from different ports of call abroad to Detroit for

years where her relationship with Sam blossomed and grew. Viola had long ago

converted to Islam but was no burqa wearing fearful woman. She favored long, ornate

African inspired clothing with traditional head covers but no blinders allowing

her pretty face to shine on the world.

All of us piled into the car and headed over to Lennox Ave. to see the famed

sights in Harlem including the musical heartbeat of it all the legendary Apollo

Theatre. Wilt Chamberlain’s equally famous bistro, ‘Big Wilt’s Small’s

Paradise’ at 135th St. and 7th Ave. which in the 60’s was

the hot spot for entertainment

and dining was almost empty soon to be closed but we went inside anyways. When

Ed Smalif opened it in the 1920’s “Smalls Paradise’ quickly became the anecdote

to the uptown clubs that still were off limits and segregated. What a scene it

must have been as the waiters and waitresses all sang and danced, the food was

traditional Southern Soul Food fare, the stage hosted everyone who was anyone

from this era and the dance floor literally vibrated with shimmering, graceful

figures in motion.

There was a parade that day the theme of which was not clear to us as

perhaps it was just another burst of the culture but rumors had it that

Muhammad Ali, fresh off his knockout in Zaire Africa of George Foreman, would

be in attendance. There were street vendors selling Ali T-shirts, pins and

posters and I regaled our group and them with my Ali impersonation to their

howling delight. “Ali goes to meet Frazier but Frazier begins to retreat…If he

goes an inch farther he’ll end up in a ringside seat!” What I cherished and

remember most was that I was the only white person except New York cops

anywhere to be seen.

It was our last night at the Wellington and we planned on hitting the

road at dawn the next day so everyone ate early and retired to their room. I

had asked to stay on an upper floor where if inclined, I could practice all

night and around eleven or so after about an hour of scales and long tone

exercises stopped to take a sip of my last vestiges of Martell cognac.

There was a soft knock on the door and I looked through the door viewer

to see a quite old black bell-hop in full dress uniform. Hoping that he wasn’t

sent to tell me to stop playing for some reason I opened the door.

“Boy, y’all got a nice fat sound. I thought it was a tenor it’s so big

and dark.”

“Thanks man!”

Eyeballing the Martell I offered him a drink which he gladly took then

said, “I’m an alto player myself. Mind if I show you a thing or two?”

I handed him the horn and neck strap and without even a note or two to

warm up he began playing in a feathery, bright sound some be-bop followed by a

soft ballad. I was mesmerized and as he handed me the horn back he said

solemnly, “Keep practicing, I got to go back to work.” I was dumbfounded,

inspired and intimidated all in the same moment.

If this old man with sad marbled eyes and slumped shoulders could play

like that maybe I better find something else to do was my overriding thought,

emotion and epiphany.

We drove through New York into New Jersey as one of Sam’s students who

lived in an affluent suburb of Cherry Hill had invited us to stay at his

parents’ palatial home on our return to Detroit. Jimmy Allen had volunteered to

drive late in the day and I recall Sam saying to just stay on I-275 and to wake

us when he saw the signs for Cherry Hill exits. It was about two hours away and

a straight shot line drive and within a few minutes the rest of us were fast

asleep. Its human nature to sense that something is amiss even when sleeping

and I awoke to find us no longer on the flat interstate but on a winding

two-lane road in high mountainous elevation in a forested area with dense fog

and limited visibility.

“Where the hell are we Jimmy?” asked Sam, adding, “Did you get off the

freeway for some reason?”

Now driving about ten miles per hour with his head stuck out the window

due to the fog Jimmy said in classic sheepish style, “I guess so!” He claimed

he saw a sign directing him to Cherry Hill and admitted to being lost. We

pulled over to the side of the road and started looking at maps and there was

no one around to ask for directions. Right on cue a New Jersey State Trooper

pulls up behind us with his lights on and peers into the Buick to see three

black men and yours truly grinning like pole cats.

“What’s going on here? Are you gentleman lost?”

Fearing that he pegged us as lying in wait robbers on a stake out drive I

murmured, “No officer, I’m Patty Hearst and these guys are the SLA!” My gallows

humor worked like a charm and after running our drivers’ licenses he kindly

directed us back to the interstate. Two days later we were back in Detroit but

something had indelibly been altered and changed forever.

Chapter Seven

The winter of 1976 in Detroit was one of the coldest and snowiest on

record and other than my daily interaction with Visions and the others out in

Rochester I was as stale as week old donuts. Everything but the music seemed

dead or dying and the City itself was on life support.

I would query Sam constantly about why he would stay in Detroit and not

go to either LA or NYC in order to “make it.”

“Make what? Do you think that money or commercial acceptance are any of

my goals? They are not and you know this. I tried that shit years ago when I

traveled with Alice Coltrane, Pharaoh Sanders, Milt Jackson and Horace Silver and

it only served to hold me back!”

“From what?”

“From my own personal accomplishments and destiny. I can’t do that

playing for others or worse trying to write for the radio. If it happens great,

but it’ll only happen on my terms with my own music. Understand me, I’m content

and more than OK with it too.”

Soon after the New Year I packed up and hopped into my VW van and headed

back to California. The next time I would see Jimmy would be in Harper Hospital

two years later on his deathbed suffering from cancers all over his precious

body. Sam and Pick along with new replacements at piano (Mike Zaporski, others)

and drums (John Knust, others) were still in the basement producing fabulous

new music and shepherding the young upstarts. In 1979 I returned briefly to

Detroit with my first wife and one year old daughter Naima named in honor of

Coltrane’s haunting ballad extraordinaire.

The year before in Hawaii I had recorded two sessions at Jimmy Linkner’s

Trident Pacific Studio and had been performing with my own quartet around

Honolulu. I had buckled down and was practicing faithfully as never before

following all of the lessons and advice that Sam had given freely to me. When

my wife announced she was pregnant the gypsies decided to flee the Island and

return to Monterey for perceived better opportunities and to be closer to

family.

That August (8-10-1978) in the entertainment section of the daily Honolulu

Advertiser Star Bulletin they had a little piece that read, “Mark Paul

Brown and his hapai (pregnant) wife leave this week for the Mainland where he

hopes to interest a major label in his recent recordings including the song

aptly titled, “Tune for The Unborn Child.” Like a ballplayer who has one good

year in the majors then falters and roams around the minor leagues until he

finally gives up hope and goes back to pump gas, I had no idea that I had

already reached my personal pinnacle as a saxophonist. Perhaps it was the

foolishness and allure of ‘Making It” and the predictable disappointment when

falling short. More likely though it was the lacking gene of true artistry and

commitment that Sam Sanders spoke of.

Our paths continued to cross and we always stayed in close touch. In the

1980’s he and Viola visited Monterey in 1984 and we drove up Highway 1 on the

coastline from Big Sur to San Francisco only to discover that the only thing on

Earth that scared him were heights.

The following year they relocated to LA for Viola’s one year of advanced

study at Drew University. We saw quite a lot of each other and always had a

wonderful, brotherly simpatico time. In 1989 I visited Detroit and for the last

time saw Sam Sanders in the flesh. Sam had created the Detroit Jazz Center

during these intervening years which like everything he touched was unique and ahead of its

time.

The Detroit Jazz Center was both an open jazz school and concert venue

that showcased guest concerts by such heavyweights as alto saxophonist Jackie

Maclean, trumpeters Woody Shaw and Donald Byrd with the core house band members

being comprised of local stalwarts including his high school classmate and

Strata Records founder and pianist Kenn Cox, baritone saxophonist Charles “Beans” Boles

and notable Strata Records players like Charles Moore (trumpet), drummers Danny

Spencer and Bud Spangler to name a few.

Soon thereafter they moved to Dakar Senegal and once in a blue moon we

would talk on the phone. He died there October 18th, 2000 and over

3,000 adoring people attended his funeral. During his time there he had started

so many music programs and had mentored the first generation of Senegalese jazz

musicians. The loyalty that his core band members had for Visions and their

work was so strong that his pianist and eventual arranger Mike Zaporski

accompanied them to Senegal and stayed for three years before beginning to

shuttle back and forth from Detroit where he still combines playing and

teaching. His ensemble is, in tribute, called “Future Visions”.

Viola became

the founder and Executive Director of the Women’s Health Education and

Prevention Strategies Alliance (WHEPSA) and 10,000 Girls Program in Kaolack,

Senegal, which

has educated multitudes of young girls shut out of the educational systems and

endures to this day. When they first bought their home and property and emigrated

full time circa 1990 they both had intended to ‘retire’.

Chapter Eight

Around 2002 I read the book ‘Chasing the Trane’ by JC Thomas considered

to be the most comprehensive and authentic of all the biographies written about

Coltrane’s life and times. In it he recreates the scene in the early 1950’s

when he was starting out primarily playing clubs in his then hometown of

Philadelphia PA such as the ‘Café Society’, the ‘Zanzibar’ and the dubiously

named ‘Snake Bar’. The bar owners, all white of course, had introduced a

required nightly ritual for the musicians to parade around the club after each

set gyrating, shucking and jiving like characters from Amos ‘N Andy called ‘Walking

the Bar’. It was at the very least undignified and demeaning along with not

so subtle racist overtones. The mostly white patrons just loved this circus charade

and gleefully and mockingly clapped their hands and shouted “Go! Go!” as the

musicians weaved their way around the nightclub like Vaudeville black face

plantation figures.

Coltrane needed the money and as bandleader felt a great responsibility

for the other band members livelihoods so he played along until one night one

of his heroes the great tenor player Benny Golson dropped in to hear him.

Golson was stunned and gasped, “Oh no!” and upon hearing this Coltrane, in his

customary dark suit and tie, stood up straight and ‘Walked the Bar’ all right,

straight out the front door never to stoop to this degradation and disrespect

again. Putting the book down in my lap I suddenly realized that this was

exactly how Sam Sanders lived his life and times with no regrets, apologies or

remorse. RIP my friend.

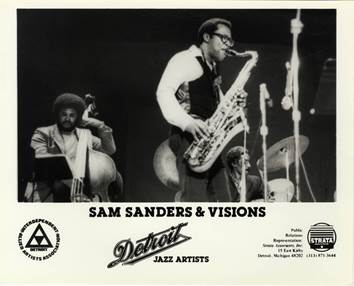

Below; Visions as they appeared on the cover of recently re-released

1978 album. Left to right;

Ed Pickens-bass. Sam Sanders

–tenor, alto and soprano saxophones. Jimmy Allen-drums.

About the Author

Mark Paul

Brown, the stories narrator, is in fact sixty-six years into his journey and

lives in Garden Valley CA overlooking a small fresh water lake in the Sierra

Foothills where he writes essays, short stories and cultural opinion pieces

with his friend Sonny and loving wife Maureen by his side. If interested in

publishing rights or to view his compilation of works, ‘Turtles, Tidbits &

Timepieces’, you may contact him at 530-621-2113 or email to: markbrown.bee@gmail.com